Featured Image: The Ueberroth Vineyard in Paso Robles, planted in 1885, is the oldest of Turley’s Zinfandel holdings. These vines are ungrafted, head-trained, and dry-farmed.

Since its earliest mentions in horticultural catalogs of the 1820s, Zinfandel has been claimed as America’s own wine variety. Long steeped in myth and speculation, its arrival to the United States was likely as a nameless import from the Schönbrunn Imperial Nursery in Vienna. With no known link to the Old World for 120 years, Zinfandel – bold and celebratory, versatile and vigorous – solidified its identity as the core of domestic wine culture. By the mid-1800s it was the most important and most planted grape variety in America. As the men and women of the Gold Rush headed west, so too did Zinfandel, providing them the fortitude to brave the elements and seek their fortune in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The vines were hardy enough to survive the hot days and cool evenings – and, most importantly, Zinfandel was vigorous enough to support the large number of new settlers.

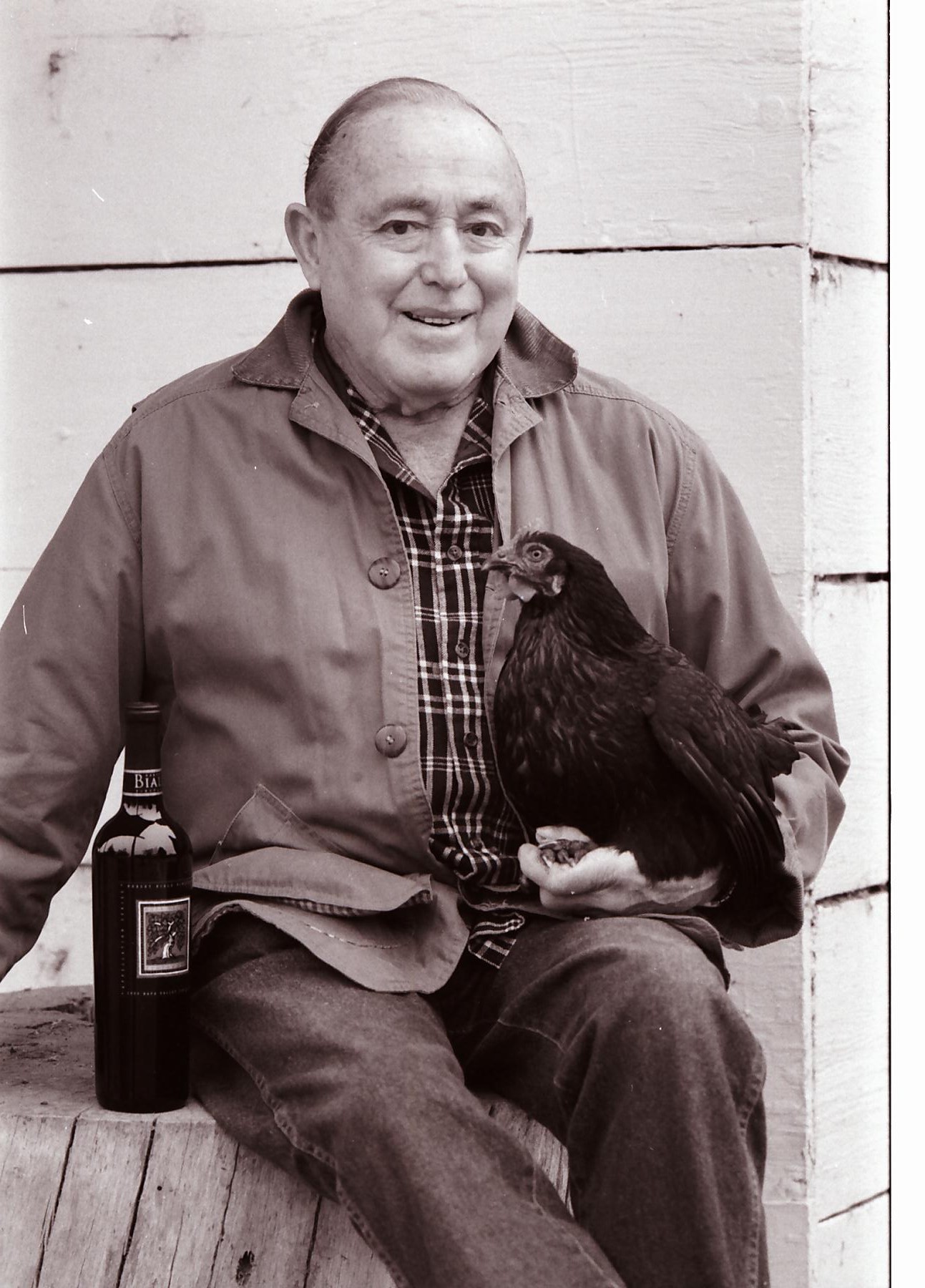

While most vines were destroyed by phylloxera in the late 1800s, Zinfandel vines were among the first to be replanted on rootstock (St. George), beginning in 1885. Again by mid-century, it had become Americas most planted variety and the backbone of wine production in the country. Zinfandel was shipped east to wineries from the Ohio Mid-Valley to the Finger Lakes, where wineries added their own labels and sold it as “Claret” in their local market. It was during Prohibition that a 17-year-old Aldo Biale started making Zinfandel at his family’s farm. Using a “party line” to place their orders, his neighbors in Napa referred to these jugs of his coveted wine by the code-name “Black Chicken.” The 2014 Black Chicken is one of the best wines we have tasted from the Biale Winery in two decades of partnership.

Today, our vintners like Tegan Passalaqua of Turley, and Bob Biale of Biale Vineyards, are committed to preserving these old-vine vineyards throughout California, and offer a new audience a glimpse into American wine heritage. These vines serve at once as time capsules and contemporary voices. The term “Old Vines” is defined by the Historic Vineyard Society as a vineyard whose original plantings date to no later than 1960, and at least 1/3 of existing vines can be traced back to the original planting date. Our friends, Timm and Sharon Crull at The Terraces, sustainably farm Zinfandel on a swath of land in the eastern hills of St Helena, built on a 130 year farming legacy. As we head toward the eastern reaches of Napa Valley, we find Jay Heminway, who planted his Chiles Mill Vineyard in 1972 with the help of his good friend, iconic chef Alice Waters. Green and Red Zinfandel was served by the glass at Waters’ Chez Panisse for years, illustrating that well-balanced Zinfandel complements progressive and foundational American cuisine. Jay continues to farm on the red volcanic soils of his estate and produces some of the most sought-after Zinfandel in the Valley.

Our newest partner in Sonoma County is an old friend – and a familiar name to the Zinfandel community. Ehren Jordan, winemaker and proprietor of Failla, last worked with Zinfandel – to critical acclaim – as the winemaker of Turley. Alongside his elegant Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, Ehren’s DAY Zinfandel is largely a celebration of Sonoma County’s nuance and his intimate relationships with various vineyard-partners. DAY is a return to Ehren’s roots – and California’s, too, as he explores the history of this iconic variety and how it flourishes today.

Zinfandel thrives in diverse climates, from Paso Robles to the Russian River and Napa. It’s best when left alone to self-regulate crop yields, often by being dry farmed, head-pruned or trained to “California sprawl.” It produces lush, fruit-forward wines that vary in alcohol levels and appeal to a wide range of consumers. But how did Zinfandel become this folk hero of American viticulture? The answer may be in a relatively recent discovery by ampelographers. Originally believed to be a descendant of Italy’s Primitivo, Zinfandel was later connected by geneticists to the Croatian variety, Crljenak Kastelanski. Further investigation has traced its origins to Tribidrag as far back as the 1400s. Zinfandel’s triumph in California, then, is only the end of a long journey: it has spent centuries adapting to myriad growing conditions, composing a history of resilience now reflected in its genetic bank, and – at last – in our glass.