If you ever get the privilege to visit a kura, as you are led through the rows of fermenting tanks, stepping over hoses and watching your breath form in the chilled air necessary to keep the huge cauldrons of rice moromi bubbling at a slow and leisurely pace, you might just start to catch a whiff of fresh apples in the air. Or the smell that comes off of a mango rind. The toji brewmaster might climb a wooden ladder up to the edge of a tank, dip a ladle in to catch some of the bubbling white liquid, or maybe squat down next to a sake press the size of a school bus, place a large porcelain cup next to the stream of fragrant liquid gushing from its base, and use it to scoop out a small portion for you to taste.

That fresh sake, pulled in infancy from the tank, or early youth from the press, will show its vitality as it bounces around your mouth: the impact and flavor are immediate, the flavors and aromas bright and tingling, the energy is palpable.

When opening up a bottle of mature sake at home or in a restaurant, it has usually grown up a bit from its infancy in the brewery. It still retains energy and excitement– but has grown more patient and articulate. Unlike the teenager it was who rushed to tell you everything at once, it is now more eloquent and expressive, and opens up more slowly, but might just have more to say.

Up until recently most of the sake released was the latter kind, carefully stored in tanks or bottles for several months to let its initial exuberance quiet down and its structure to develop and grow more refined. In addition, youthful sake was sent to charm school, the flavors were adjusted by techniques found to make it light and elegant. The terms for sake kept as much as possible in its fresh and young state are basically all badges of rebellion against those techniques. These processes sometimes appear alone but are often clustered as a pack: muroka nama genshu.

For at least fifty years sake brewers have been using activated charcoal to clarify and remove off flavors from sake, similar to the charcoal used in household tap water filters. This process is roka, but many breweries like to skip the step to leave in color and depth of flavor, a process known as muroka or non-carbon filtered.

An even earlier way of making sure sake was stable and wouldn’t spoil quickly is a process more familiar to us: pasteurization. At some point in the mid-1500s, 300 years before Louis Pasteur looked at microbes under a microscope and started ruining our milk by heating it, sake makers discovered that gently heating it to about 150F made the sake last much longer. It became standard practice and is now standard for most sake. But with improvements in storing and shipping sake at cool temperatures in recent decades, it has become possible to ship out unpasteurized, fresh sake known as nama that retains many of the appealing brashness and vitality of sake straight from the brewery.

Lastly, sake naturally tends to ferment to a spine-tingling alcohol level of 18-19% and sometimes higher. This is usually brought down by a slight water addition to a more food-friendly 15-16% which also lightens its texture and body. But sometimes even conservative brewers like to rock out and let their sake express itself a bit more leaving the sake undiluted and untouched or genshu.

While some of the larger, more established producers have tiptoed into these styles by making mostly high-alcohol flavor bombs, many smaller breweries are now crafting young sake that is energetic while still showing remarkable complexity and depth of flavor. While the finest and most elegant sake is released after aging, we now also have many sake that show amazingly well when still young and fresh. What they may lack in subtle finesse they make up for in sheer energy and vitality.

Below find five terrific examples of sake that expand the possibilities for Japan’s national beverage:

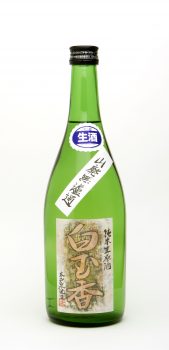

Junmai Ginjo Muroka Nama Genshu Sake, ‘Moon Mountain’s Dew’, Hakurosuishu

This is made in Yamagata, which is known for fruity, dynamic and floral sake. That characteristic fruitiness is given an extra zip by releasing this sake as a muroka nama genshu. Bright acidity, notes of fresh herbs and tart fresh fruits make the Hakuro Suishu super dynamic and drinkable.

Junmai Arabashiri Kimoto Muroka Nama Genshu Sake, ‘Sublime Beauty’, Tae No Hana

Rumiko Moriki is Japan’s first female master sake brewer, something that takes grit and determination in this traditional society, so it’s no surprise she would make sake that is just as groundbreaking. While most junmai level sake is made from rice milled to 70% or less, for this unique expression she is using almost all of the rice grain, leaving it at 90%. By skipping charcoal filtering and leaving the sake muroka it keeps dark flavors of cremini mushrooms and a powerful rice bran acidity.

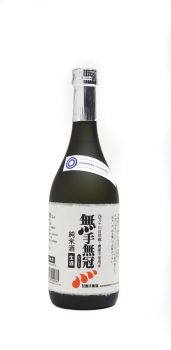

Junmai Muroka Nama Genshu Sake, Mutemaka

What happens when a young nama sake, almost always consumed fresh, is allowed to mature a little bit? The answer is apparently: delicious. The signature Junmai Muroka Nama Genshu from Mutemuka has liveliness and energy, but the sharp spicy nama qualities are softened by six months of aging at room temperature, giving it qualities of cacao and fresh hazelnuts.

Yamahai Junmai Muroka Nama Genshu Sake, ‘Fragrant Jewel’, Hakugyokko

The Kidoizumi Brewery doesn’t follow convention. For years they found methods to source the best sake rice farmed in a time-honored manner, skirting the big agricultural associations. While most other brewers are fussing over low temperatures, they embraced the relatively warm climate of their native Chiba to invent a new method of “Hot Yamahai” which gives this sake a depth and power balanced by incredibly delicate tropical fruit notes. Rarely do muroka nama genshu this big and rich show this much complexity.

Junmai Muroka Nama Genshu Nigori Sake, ‘Forest Spirit’, Soma No Tengu

Given that the Uehara Brewery sticks to time-worn methods, brewing sake in traditional cedar vats instead of modern steel tanks and is one of the very few sake producers using yeast native to their brewery instead of a standard cultivated strain, it isn’t a surprise they also leave the sake as untreated as possible, not diluting the final product or thinning the character with charcoal filtering. They even filter more roughly than normal leaving a touch of rice sediment in the brew that gives it a touch of body and texture. The results are citrusy, zesty and compelling.