What is the future of sake?

The past is easy to talk about with sake. Its origins stretch back millennia, almost every single brewery making sake today has a history of at least a century, many stretching back hundreds of years. But what can sake be?

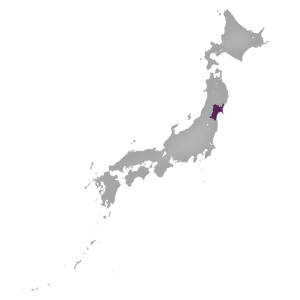

There are few people who have thought harder about this question and done more to push it forward than Iwao Niizawa, the owner and former brewmaster of Niizawa Jozoten, his family’s sake brewery in northern Miyagi Prefecture.

When we first paid Niizawa Brewery a visit a couple years back we weren’t sure what to expect, but an enthusiastic young team, mostly consisting of workers in their 20s, certainly wasn’t it. Sake making has traditionally been a tough, blue-collar profession, and in our visits to sake breweries over the years we’ve often encountered tough older men who picked up the work to make some extra money in the cold months while their farms lay fallow. This team consisted of young men (and women!), enthusiastically doing the tough work of steaming rice, mixing heavy koji rice by hand, stirring huge tanks of fermenting sake and cleaning — always cleaning.

Given the blue-collar nature of the business, breweries are often cobbled together affairs with layers of the past scattered about. A 100 plus-year-old original wooden building may have a new steel wing to create more space for a bottling line. A gleaming new press will set next to 80-year-old fermenting tanks. Niizawa Jozoten, on the other hand, is a brewer’s dream, with plenty of space, new equipment, and bright, clean surfaces. They are adding team members and improved equipment all the time. This is all the more remarkable when you consider the company was on the brink of disaster just a couple years ago, in 2011.

Iwao Niizawa is the fifth generation of his family to run the brewery, which was started by his great-great-grandfather is 1873. His story is emblematic of many sake makers of his generation. After decades of the biggest sake makers dominating the market with cheap and unappealing sake, small breweries like themselves had been almost completely marginalized. Along with other sons of sake making families he attended the brewing science program at Tokyo’s Agricultural University (affectionately called NoDai) where in addition to occasionally studying he ate and drank his way across the city, enjoying affordable sushi in the Tsukiji Fish Market.

Upon his return to take over the family business in 2000 he found the brewery on the brink of bankruptcy, and began to drastically change their operations. All his time spent in Tokyo’s bars and restaurants had given him insight into a direction for the business. Chef after chef would tell him they loved the elegance of fragrant ginjo grade sake that had become popular, but that it didn’t particularly match with their food, and that people rarely ventured past one glass. While it may seem obvious, few brewers were concentrating on making high-grade, elegant sake that specifically leant itself to food.

With the firm goal in mind of creating a complex sake that was restrained enough for great Japanese cuisine, Niizawa not only committed to sourcing sake rice from some of the best farmers in the country, he rethought the brewing process from the inside out. Unable to afford hiring a toji brewmaster he took on the job himself.

The Hakurakusei Series

Sake is usually adjusted in all sorts of ways after pressing to produce a more consistent result. The liquid is passed through activated charcoal to strip out off-flavors, it is pasteurized to make it smooth and last longer, and different batches are blended to achieve uniformity. Niizawa found these blunted the finer qualities, so he took out all charcoal filtering, switched to one gentle pasteurization instead of the standard two, and brewed his batches with such consistency that blending was unnecessary to hide flaws.

While these techniques aren’t uncommon, they are usually used for bold, rich styles, which proudly announce their use on the label with words like muroka, nama, and ki-ippon. Preferring to let the sake speak for itself Niizawa chose a simple and classic label design of black calligraphy on a white background, and no other information other than the sake grade. The name he chose was a reference to a local Miyagi legend of a man with a keen eye for finding quality in unexpected places: Hakurakusei, a connoisseur.

While Japan has its fair share of well-known restaurants with Michelin stars and magazine spreads, the true heart of Japanese cuisine is in the thousands of small establishments that are a single chef’s labor of love. They seek nothing more than to build a loyal following to keep the business afloat and allow them to pursue their craft. Niizawa would connect with these places one by one, and Hakurakusei quietly found its way into one 12-seat restaurant after another, the owner enthusiastically sharing this sake he had discovered that let the subtle flavors of Japanese cuisine shine. It didn’t announce itself with colorful labels, huge aromas or punchy flavors but would slowly open itself up over time. It began to acquire the moniker that many people refer to it as today: saiko-no-shokuchu-shu or “ultimate food sake.”

In many ways Hakurakusei remains the connoisseur’s sake, passed through the whisper network of fine Japanese restaurants, but it was a sake that Niizawa approached as a purely technical challenge that gained him the most notoriety.

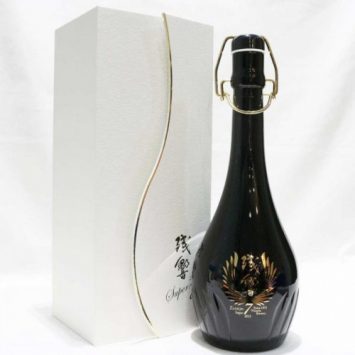

Zankyo Super 7

In the past couple decades makers had been topping one another with sake made from progressively more highly polished rice. In addition to the difficulty of milling down a rice grown to its center without having it crack, these tiny grains are difficult to handle and grow koji on. Niizawa never bothered to polish below a standard 40%, but set himself the challenge of seeing just how small the rice could get, and how it affected the flavor.

Using a local Miyagi rice type called Kura no Hana that could keep its structure at high polishing, he was able to make a sake from rice polished to just 7% of its original size. The result, known today as the Zankyo Super 7, was bewitching, even more fleeting in flavor and subtle than his previous efforts, and the incredible technical achievement alone made news outside the sake world.

New Beginnings

Having turned around the fortunes of his family business, established his reputation among the small restaurants he loved dearly and achieved incredible results as a craftsman of sake, things were looking good until disaster abruptly struck in 2011.

It is hard to overstate the impact of the Great Tohoku Earthquake of 2011 on Japan. Even though it hit the far north it impacted the entire country, buildings leveled in the shocks and aftershocks, tsunamis devastated coastlines, and the power grid was disrupted for much of the country, with Tokyo experiencing rolling blackouts for weeks. The stout little building that had housed Niizawa brewery for 138 years collapsed on itself, as the earthquake struck on March 11th, wiping out almost the entire year’s worth of work. The original brewery was ruined, and rebuilding would be costly and difficult.

Moving quickly Niizawa found a defunct brewery about an hour’s drive from the original location. Unlike their original location in the town of Osaki, this was in a remote valley high in the mountains, with no other buildings around and a pure, local water source. With the help of many other small sake breweries around the country he built out the brewery he had always wanted, open and clean, allowing he and his team the freedom to concentrate on the nuances of handmade sake. Within nine months they were making sake again.

Moving quickly Niizawa found a defunct brewery about an hour’s drive from the original location. Unlike their original location in the town of Osaki, this was in a remote valley high in the mountains, with no other buildings around and a pure, local water source. With the help of many other small sake breweries around the country he built out the brewery he had always wanted, open and clean, allowing he and his team the freedom to concentrate on the nuances of handmade sake. Within nine months they were making sake again.

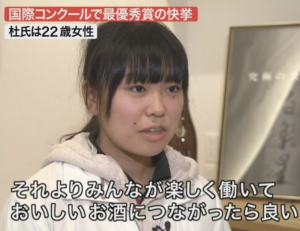

The support that he received from other small breweries gave Niizawa a newfound appreciation for the importance of community and teamwork, and his next project may prove to be his most lasting legacy. Sake is a labor-intensive beverage to make, and he recruited promising young men and women to join his team, prioritizing passion and skill over Japan’s traditional deference to experience and seniority. That was the team in place when we visited them a couple years back, and the energy was palpable. At the time Niizawa had made a major change to his team, quietly appointing a new toji brewmaster to head production while he moved to a more supervisory and planning role. As always, he preferred to let the quality of the sake speak for itself and didn’t make any sort of an announcement.

In the Fall of 2018, when the major tasting competitions are held for new sake, items from Niizawa were once again on top in several categories. The press and industry was shocked when the required name of the brewmaster on the lists wasn’t Iwao Niizawa but Nanami Watanabe, a 22-year-old woman who had been working at Niizawa Brewery for several years and was an alumni of the same brewing science program as Niizawa. In the Junmai category their sake was ranked 2nd out of 456 entries, as ranked by dozens of judges all tasting the sake blind. The press went wild, as she was the youngest person working as a toji brewmaster at the time.

When we had a chance to ask Niizawa-san about his decision he said that he had talked to his senior people for months about who the best person to lead the team would be. Watanabe’s name came up often for her work ethic, her sensitive palate, and intuitive understanding of fermentation. Just as Niizawa had taken over brewing in his early 20s he felt confident she was simply the best person for the role.

Oh, and did I mention our number two brewer is a young American?

For years the sake industry has been stuck in the past, and not always to its benefit. Workplaces bound by rules and traditions can ultimately stifle a focus on good brewing. Brash and attention-getting styles made an impact and showed off the skill of the brewer, but ignored the important role of sake as a supportive companion to excellent food. For twenty years Niizawa-san has been innovating and overcoming disaster by concentrating on the results of his work, finding the best way to get there, and letting the quality of sake quietly speak for itself.

Tokubetsu Honjozo Sake, Atago No Matsu

- Elegant, creamy, light herbal notes of sage and wild strawberry with a lemony finish.

- Originally only sold around the brewery, Atago no Matsu quietly acquired a reputation by word of mouth and is now enjoyed around the world.

- Pair with dishes with a bit of fat or creamy texture. Fresh large oysters, yakitori skewers or grilled salmon in a light cream sauce.

Junmai Ginjo Sake, Hakurakusei

- Slightly fuller and chewier than the Hakurakusei Tokubetsu Junmai, it shares the house style: clean and zippy and remarkably food friendly.

- Enjoying this out of glassware with plenty of room to breathe can really unlock its nuances, once you catch a touch of grapefruit or melon it disappears.

- Just full enough to stand up to richer and sweeter foods like simmered Japanese nimono dishes or to cut through chicken liver mousse.

- Made from lesser known varietal Kura no Hana rice milled to 55%.

Tokubetsu Junmai Sake, Hakurakusei

- Classic example of a modern sake style, the Hakurakusei Tokubetsu Junmai is laser focused, a clean, direct sake bursting with vitality.

- Nuances of apricot and peach and faint notes of citrus zest.

- Fresh and alive with a tingly finish, this sake is designed to stimulate the appetite and to complement light and delicate dishes without overwhelming them.

- Particularly good with a variety of sashimi or summer salads.

- High quality Yamada Nishiki rice from Hyogo prefecture milled to 60%.

Junmai Daiginjo Sake, Hakurakusei

- For his Junmai Daiginjo Niizawa-san has chosen to use heirloom Omachi rice milled to 40% which gives this graceful sake a slightly herbal and savory quality.

- A light bodied sake with a delicate balance of flavors and textures, this is the pinnacle of the Hakurakusei series.

- An elegant sake ideally matching a range of cuisine.

Junmai Super Daiginjo Sake, ‘Super 7’, Zankyo

- Zankyo means literally “Reverb” or “Vibration”

- Incredibly light and delicate structure, very fleeting textures, flavors and aromas that characterize the very best sake: always just beyond your reach.

- Citrus nose like freshly expressed grapefruit peel, young pear tones.

- A masterpiece of sake brewing, the first sake made from rice polished to just 7% of its original size, made by continuously milling rice for over 10 days.

- Kura no Hana rice milled to 7%

PRESS

One of Jancis Robinson’s six “Sake Picks” for the Financial Times, and the sake she dubbed “The star of the show”