The world of Japanese sake may seem like a lot to take on: the labels are beautiful but written with a tangle of unfamiliar characters! The very best sake has a haunting flavor that always seems just out of reach and always just beyond description. Like its alcoholic cousin wine, description of sake can easily slide into poetry and metaphor. Where does one even start?

Below we have a few suggested starting points for getting acquainted with sake. We’ll cover several major premium styles, as well as a range of the textures and flavors possible in fine sake.

The easiest way to find quality sake is to seek out one of the major ‘premium’ categories. To reach any of these premium levels, sake has to pass certain strict requirements for production. Similar to Germany’s famous beer purity law the Reinheitsgebot, sake with premium designation can only contain four or five ingredients. The categories Junmai, Tokubetsu Junmai, Junmai Ginjo and Junmai Daiginjo can only contain rice, water, yeast and koji rice. If the label has Honjozo, Tokubetsu Honjozo, Ginjo or Daiginjo the sake also contains a touch of distilled alcohol that gives it a smoother texture with more focused aromas. In short, if the label has the word Junmai it is a premium sake with no added alcohol, and if it contains the word Ginjo it is at the height of premium sake and will generally have more depth and complexity.

A great starting place is the Yuki Otoko Junmai a clean and easy drinking sake from Aoki Shuzo in Niigata Prefecture. Every winter for centuries the people of Niigata have survived the harsh deep mountain winters where heavy wet snowpack often piles up 8 to 10 feet high. The sake is named for the local legend of an Abominable Snowman or Yeti who haunts the deep mountains but has been known to help lost travelers.

The same snow that creates the tough and resilient culture of Niigata makes for clean and incredibly soft water ideal for making Yuki Otoko, and is the basis of the classic regional style: clean dry, not very aromatic, with a faint sweetness of rice. The Yuki Otoko is a model Junmai style sake, it is smooth and drinkable with a direct food friendly flavor without a lot of flash and fanfare.

For a contrast from an easy drinking Junmai try out the Midorikawa Honjozo, also from snowy Niigata. Like the Yuki Otoko it is clean, light and drinkable but milder and creamier in flavor. The addition of a little distilled alcohol gives this sake a smooth, silky texture and a light weight.

The Midorikawa Honjozo also shows off the range of temperatures you can enjoy sake at. Tight and focused while chilled, when warmed it opens up developing a buttery sweetness but retaining a snappy finish. The perfect accompaniment to yakitori or classic grilled chicken.

Moving up in class we have two Junmai Ginjo grade sake that show off the diversity within a single classification. To reach a higher classification in sake the breweries will use rice grains that have been more highly milled. The center of the grain of rice is where a sake yeast can start to find subtleties that with the right touch can evoke fruit flavors and delicate floral aromas. The structure can become more layered and the texture more nuanced. Sake made from rice milled down to just 60% or less of its original size can start labelling itself as a Junmai Ginjo or Ginjo, and the jump up in category shows a noticeable increase in delicacy and subtlety.

Exhibit A is the Gikyo Junmai Ginjo, a stunning example of premium sake making. Carefully crafted in the centrally located prefecture of Aichi by Yamachu Honke, the brewery has a reputation for obsessive attention to detail. They use Grade A Yamada Nishiki rice from the Tojo area of Hyogo Prefecture to craft this sake. Trust us when we say this is a big deal in a civilization literally built on rice. The Tojo farmers trust only a few breweries to treat their rice with the care it needs to bring out its most expressive qualities, and the Gikyo certainly does that. A laser-like structure starts with a slight evocation of fruit and moves into hearty notes of toasted wheat. Gikyo really shows us the possibilities of a premium sake, but there is a lot of variation even within this one category.

In another corner of the Junmai Ginjo category is the Okarakuchi or “super dry” Toyo Bijin Junmai Ginjo. Despite using the same Yamada Nishiki rice as the Gikyo the brewer Sumikawa-san has elected to keep that characteristic fruitiness just at the front of the sake, evoking a whiff of just ripe melon and banana before cutting into a rippingly super dry finish that evokes allspice and nutmeg. It packs all the subtleties of the Junmai Ginjo style into a remarkably compact package and creates a dry spicy finish unlike anything else we’ve tried. If you’ve ever doubted the ability to pair sake with steak or roast pork this may just change your mind on the subject.

So what could top these sake? For a long time the industry just called all sake sake made from rice milled down to 60% and below as Ginjo to let the drinker know they were getting into a category featuring light and nuanced flavors and fine aromas. As sake makers became more and more ambitious techniques were refined, rice was milled down even further, and suddenly the subtle Ginjo category had reached ethereal new heights. To acknowledge and differentiate this delicate new style the sake makers started to dub them Daiginjo, literally “great Ginjo”. This new category is strictly defined as sake made from only water, yeast, koji and rice milled down to just 50% of its original size or more. So literally taking the total amount of rice you’ve purchase and milling it down so you’re only using half of it or less to make sake.

As you would expect, sake in the Daiginjo grade is not only fine and ethereal but incredibly tricky to make, requiring all of a sake brewer’s skill. There is no room for error with these sake, the slightest error in fermenting or cleanliness leads to unbalanced flavors that throw off the entire sake. This is where a sake brewery displays its mastery of craft to produce a poem of immense subtlety crafted from simply microbes, rice and water.

An excellent place to explore this vast category are the legendary Kotsuzumi sake made in Hyogo prefecture, home to some of the country’s greatest rice farming. The Kotsuzumi Hanafubuki ‘Shower of Blossoms’ Junmai Daiginjo is a sake of restraint and poise. Unlike most Daiginjo it is clean and clear with mild aromas. The brewery Nishiyama Shuzo takes great pride in using only locally grown Gohyaku Mangoku rice and leaving the sake in as close to a natural state as possible by refraining from filtering or over pasteurization. This sake is vivid in its texture, lithe and supple like sipping from a mountain stream.

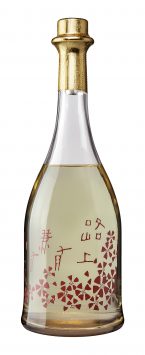

As a terrific comparison the very same brewery makes another Junmai Daiginjo grade sake, the Kotsuzumi Tohka ‘Peach Blossom’ Junmai Daiginjo. It is made in the exact same method as the ‘Shower of Blossoms’ with the only difference being the rice. The brewery carefully grows locally famous Hattan Nishiki on its own rice paddies, a varietal that can produce beautifully deep and rich flavored sake. The water, yeast, koji and production are identical to ‘Shower of Blossoms’ but the local rice shines through. True to its name, the color of the ‘Peach Blossom’ is a gorgeous lightly pinkish orange, the aromas follow suit with evocations of peaches and white flowers, and the liquid itself has body and depth that seems to vibrate on the tongue. The flavor carries a light sweetness that always seems just out of reach, forcing you to take another sip to search for it.

We’ve reached the poetic pinnacle of sake, the stuff that has seduced the Japanese for centuries and inspired some of their greatest writers to tipsy insights on nature, humans and the fleeting nature of time. It’s no surprise that the name for Kotsuzumi itself was coined just over 100 years ago by a haiku poet. Over a night of drinks and poetry with the brewery owner the renowned writer penned a quick ode, trying to describe the power and emotion he sensed in his cup. He called the sake a kotsuzumi, a little drum, positively vibrating with energy.