Above: Nihonbashi. Print by Utagawa Hiroshige.

Japan is a nation uniquely familiar with disaster, and it informs so much of their culture and outlook on life. Being perched at the end of the earth on a geologic fault line, earthquakes are a fact of life, and the typhoons that arrive each year from the south bringing flash floods and lashing winds. The steep slopes that make up the country’s landscape bring with them landslides and avalanches. Yet amidst this Japan has been able to sustain many institutions for centuries, including many sake makers. We’d like to highlight a couple of those success stories.

Kenbishi is passed around like a secret handshake in the sake world. You meet someone new: a toji brewmaster or the manager of a sake bar. You talk about how you got into this world, and which sake you personally like. You might mention some new exciting maker, that 29-year-old who took over for his father on short notice and in three years has given their obscure brewery an international reputation. But then you might pause, size up the person you’re talking to and venture out: “They’re pretty big, but you know what sake I love? Kenbishi.”

We’ve mentioned this to some of the smallest, most dedicated artisanal sake makers in the world and without fail the answer is the same. “Kenbishi does things right. They’re awesome.”

It’s impossible not to slip into hyperbole when discussing them. They are one of the biggest sake makers in the world, somewhere around number fifteen in production, and yet their methods are more traditional and hands-on than most makers a fraction of their size. They have been in continuous business since 1505, with the same diamond logo, and the sake has barely changed over that time. Everything they make drinks bold and rich, with layers of nutty umami. They bring the flavors of the past to the present and into the future.

Looking into their history the company has weathered disasters for centuries. When Kenbishi was founded in 1505, Japan was in the middle of the bloodiest period of its history: an era known as the Warring States period. Local clans and warlords vied for power, and civil war and unrest spread throughout the entire country. Despite this Kenbishi grew and survived to see the country unified under the Tokugawa clan in the early 17th century, which led to 250 years of peace and prosperity.

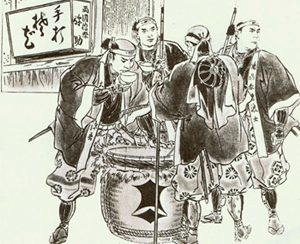

Even in times of peace there were massive challenges. In 1633 earthquakes devastated the rice harvest and the government cracked down on sake production as an unnecessary use of the grain that forms the basis of the Japanese diet. However, it was in this era that the sake acquired its legendary reputation and became an icon of Japanese in popular culture. The woodblock print artist Hiroshige is most well-known for his iconic Great Wave off Kanagawa, where Mount Fuji is framed by a huge curling wave. But take a look at the first print of his series illustrating life along the great Tokaido road that links medieval Tokyo with Kyoto. In the very first print fish mongers and ladies scurry across Nihonbashi bridge, and if you look closely at the two laborers hauling a sake barrel the unmistakable Kenbishi diamond logo peeks back at you.

Over the centuries, the company passed from family to family, with the Shirakishi family taking over in 1928, and soon facing their own new set of challenges. It was badly damaged in the Great Hanshin Flood of 1938, and destroyed completely in 1945 by the firebombing raids during World War II.

Yet they have rebuilt and are still standing, better than ever, and we were lucky enough to visit Kenbishi for the first time earlier this year. We were met by owner Masa Shirakishi, who took over the business from his father in 2017. He proudly showed us just one of their four breweries and it exceeded our expectations.

In an industry primarily converted to stainless steel, the amount of wooden equipment used in Kenbishi is stunning. Vast wooden rooms for making koji, where every clump of rice is turned over by hand. They prefer to use custom wooden rice steamers because of how that regulates moisture. We have visited tiny breweries with state-of-the-art systems to control temperature in fermenting tanks, but at Kenbishi? They adjust temperature by pouring hot water into wooden dakidaru barrels that plunge into the fermenting mash; unlike metal, the wood allows the heat to release slowly.

There is a lot of talk in the sake industry these days about how all the craftsmen who know how to make these traditional wooden items have dwindled to almost none, so where were they getting all this equipment? Here is where Shirakishi-san’s face lit up. He walked us over to a separate building and flicked on the light switch. We were greeted by rows and rows of workbenches, table saws and drills. “We started our own wood workshop since there isn’t anyone big enough to make all the equipment we need. We also have started selling these to other sake companies who want to use traditional wood tools.”* Even into the 21st century, Kenbishi endures by doing their best not to change.

Later over lunch Shirakishi-san pointed out that we were close to the site of one of their earlier brewery buildings:

“What happened to it?”

“Oh, it was destroyed in the Great Kobe Earthquake of 1995.

We actually lost seven of our eight brewery buildings that year.”“That’s awful! How did you come back from that?”

“We’ve done it before. We rebuilt.”

*Just a few days later on the other end of the country on a small island in the Inland Sea we met Tanaka-san who runs Kenbishi’s workshop. Not surprisingly we were both at a summit on preserving the knowledge and techniques of building the huge kioke barrels traditionally used in sake and soy sauce fermentation.

Honjozo Sake ‘Kuromatsu’, Kenbishi

- This is the taste of old school sake: deep, rich, bursting with umami, sweetness and acidity.

- Pairs beautifully with oysters, sea urchin, tempura and even dry-aged steak.

- Made from locally Hyogo-grown Yamada Nishiki and Aiyama milled to 60% and a touch of distilled alcohol to add weight and enhance the dark aromas.

- This is a rich and savory sake that brings a suitcase of umami to the party.

Junmai Sake ‘Mizuho’, Kenbishi

- Bold and beautiful, Mizuho is carefully blended from a mix of 5- to 8-year-aged Junmai sake giving a silken texture to the stout soy and umami flavors of the sake.

- Particularly good with rich dishes like uni, toro or Hyogo’s local specialty of Kobe wagyu beef.

- Made from 100% Yamada Nishiki rice produced exclusively for Kenbishi.