The Ribeiro: would this rose by any other word smell as sweet– or even sweeter? I’m half convinced that a jazzier name alone could have worked wonders for this underappreciated denominación. As it stands, this fairly generic “Riverbank” (the literal meaning) seems a little lost in the crowd of those other nearby Banks, the juggernaut Ribera del Duero and the ascendant Ribeira Sacra. But make no mistake: some of the most compelling wines produced in Spain today hail from this sleepy stretch of the river Miño.

It wasn’t always thus. Vintners in and around the D.O.’s capital, Ribadavia, cultivated good export markets as early as the fifteenth century, winning renown for their strong, sweet, dried-grape vinos tostados. As late as the early nineteenth century, Ribadavia was one of only two Galician wines mentioned by name in André Jullien’s Topographie. Phylloxera was predictably unkind to the area, not least because replanting trends veered away from such established local specialties as Treixadura and Caíño and toward vaguely productive workhorses like Garnacha Tintorera (Alicante Bouschet) and Palomino—yes, that Palomino. Indeed, production soared as the region developed a vogue within Spain for bulk wine, leading to the current situation: known in Spain for cheap plonk, barely known abroad. But the times, in the words of our Nobel laureate, they are a-changin’, and our stable of growers– a veritable cornucopia of the Ribeiro’s choicest delights—is poised to spread the good news.

But let’s situate ourselves. The Ribeiro consists of that stretch of the river Miño wedged between the Condado do Tea subzone of the Rías Baixas and the Melgaço subzone of the Minho to the west (the former on the north bank, the latter on the south) and the Ribeira Sacra to the east. (On that information alone, it’s easy to see how the region must be understood in the context of the wider Galician renaissance). Soils, as might be expected, are basically granitic in varying degrees of decomposition, often reaching a particularly well-drained sandy texture. Slopes are not terribly vertiginous, but expositions can be excellent as terraces abound. The beating heart of the appellation, as mentioned, is the historic town of Ribadavia, situated where the side valleys of the Avia and the Arnoia meet the Miño from the north and the south. The key white grape (“the queen of the Ribeiro”, as some would have it) is Treixadura. Shrill and yowly if overproduced and/or underripe, it reaches Parnassian heights of lush, textured complexity when handled correctly. The red scene is diverse; Brancellao, Caíño and Sousón (Vinhão) rub shoulders with the more widely-known Mencía, but others like Ferrol are being painstakingly resuscitated. Such for the stage—now the players.

Could this be one of the most underrated growers in all of Spain? Luis himself would blush at the suggestion; his humble demeanor is one of the most striking aspects of his character, especially for a man widely acknowledged as one of the best, if not the best, growers in the appellation. Working since 1988 out of an adega in Arnoia built by his grandfather, Luis makes incredible Treixadura-based whites and silky, elegant reds from a smattering of varieties, old vines of which are increasingly rare. (Good thing he’s going to the trouble of massale-selection replanting of them for the generations to come.) The core holdings total merely five hectares divided among nearly a hundred (!) plots in the environs of Arnoia. (One exception is the recently-acquired A Teixa, a single site up and across the river in Ribadavia.) Like many of the finest things in life, the range is intimidating to novices but rewards close study. The Viña de Martin Os Pasás white is Luis’ only wine fermented and raised entirely in tank, and is delightfully mineral and light of foot. The A Teixa white (from the above-mentioned vineyard) is fermented and raised in a single 23 hL foudre (now seven years old), and this, combined with the character of the site, yields a much richer but still laser-precise wine. In red, the Eidos Ermos (“fallow field”) is a young-vine quaffer which still displays remarkable complexity. A Torna dos Pasás comes from slightly older vines and recives a slightly longer and more oak-influenced elevage. Both white and red reach their pinnacle in the Escolma (“selection”) bottlings. Culled from only the most concentrated fruit from the best sites, these wines are fermented and raised in barrel and only reach the market after extensive further aging in bottle. They are among the most refined treasures the country of Spain has to offer.

Could this be one of the most underrated growers in all of Spain? Luis himself would blush at the suggestion; his humble demeanor is one of the most striking aspects of his character, especially for a man widely acknowledged as one of the best, if not the best, growers in the appellation. Working since 1988 out of an adega in Arnoia built by his grandfather, Luis makes incredible Treixadura-based whites and silky, elegant reds from a smattering of varieties, old vines of which are increasingly rare. (Good thing he’s going to the trouble of massale-selection replanting of them for the generations to come.) The core holdings total merely five hectares divided among nearly a hundred (!) plots in the environs of Arnoia. (One exception is the recently-acquired A Teixa, a single site up and across the river in Ribadavia.) Like many of the finest things in life, the range is intimidating to novices but rewards close study. The Viña de Martin Os Pasás white is Luis’ only wine fermented and raised entirely in tank, and is delightfully mineral and light of foot. The A Teixa white (from the above-mentioned vineyard) is fermented and raised in a single 23 hL foudre (now seven years old), and this, combined with the character of the site, yields a much richer but still laser-precise wine. In red, the Eidos Ermos (“fallow field”) is a young-vine quaffer which still displays remarkable complexity. A Torna dos Pasás comes from slightly older vines and recives a slightly longer and more oak-influenced elevage. Both white and red reach their pinnacle in the Escolma (“selection”) bottlings. Culled from only the most concentrated fruit from the best sites, these wines are fermented and raised in barrel and only reach the market after extensive further aging in bottle. They are among the most refined treasures the country of Spain has to offer.

THE BIODYNAMIST: BERNARDO ESTÉVEZ

Formerly a car mechanic in Vigo, Bernardo Estévez began planting his own vines and reclaiming family vineyards in 2001 while learning the niceties of biodynamic viticulture. Since officially establishing his own winery in 2009, he is typically to be found not in the cellar but hand-working his mere two and a half hectares of vines. Some Arnoia neighbors express skepticism about his “practices”, but pop the cork and the results are undeniable: his Issué, an oak-raised white blend of Treixadura, Godello, Albariño and such ampelographical rarities as Lado, Caíño Blanco, and Silveiriña, impresses with its fragrant, balanced intensity. Bernardo is gaining more recognition with each passing vintage, and while quantities will always be tiny by the very nature of his mission, we can only hope the fruits of his labor will continue to reach a wider audience. In the meantime, if you have a smattering of Gallego (don’t be shy, it’s essentially Spanish with a Portuguese twist), you can enjoy his blog.

Formerly a car mechanic in Vigo, Bernardo Estévez began planting his own vines and reclaiming family vineyards in 2001 while learning the niceties of biodynamic viticulture. Since officially establishing his own winery in 2009, he is typically to be found not in the cellar but hand-working his mere two and a half hectares of vines. Some Arnoia neighbors express skepticism about his “practices”, but pop the cork and the results are undeniable: his Issué, an oak-raised white blend of Treixadura, Godello, Albariño and such ampelographical rarities as Lado, Caíño Blanco, and Silveiriña, impresses with its fragrant, balanced intensity. Bernardo is gaining more recognition with each passing vintage, and while quantities will always be tiny by the very nature of his mission, we can only hope the fruits of his labor will continue to reach a wider audience. In the meantime, if you have a smattering of Gallego (don’t be shy, it’s essentially Spanish with a Portuguese twist), you can enjoy his blog.

Proprietor Juan Míguez, native son of the Ribeiro, plied his trade as a restaurateur further afield in Coruña before turning home in search of a house wine in 1980. Finding success beyond the walls of his wine bar, he expanded his holdings, acquiring such choice parcels as the Viña Leiriña and Finca Traveselas. He’s now helming a thriving winery with new gravity-fed facilities in the town of Leiro. None of the wines see a shred of oak, and they are all refreshing, beautifully-made exemplars of the sort of digestible, low-alcohol regional specialties that shine on the table, leaving drinkers thirsty for the next glass.

Proprietor Juan Míguez, native son of the Ribeiro, plied his trade as a restaurateur further afield in Coruña before turning home in search of a house wine in 1980. Finding success beyond the walls of his wine bar, he expanded his holdings, acquiring such choice parcels as the Viña Leiriña and Finca Traveselas. He’s now helming a thriving winery with new gravity-fed facilities in the town of Leiro. None of the wines see a shred of oak, and they are all refreshing, beautifully-made exemplars of the sort of digestible, low-alcohol regional specialties that shine on the table, leaving drinkers thirsty for the next glass.

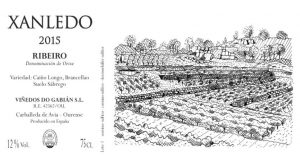

THE PHARMACIST: VIÑEDOS DO GABIÁN

José Pereiro López-Quecuty (Pepiño, for short, is a little easier) wears a few hats. Primarily, up until recently, he was one of the town pharmacists in Vigo in the Rías Baixas. In wine circles, he was known to lend a hand in the cellar of Raúl Pérez. In 2011, his own vinous vision came to fruition not with Albariño or Mencía but with the planting of a three-hectare amphitheater of Brancellao and Caíño Longo in Carballeda de Avia called O Gabián. For now, only a portion of that estate fruit is being bottled (as ‘Xanledo’), but as the roots dig deeper into the granitic sand it’s only going to get better; as it stands, the sheer elegance of the wine is already such that the lion’s share of it destined for American shores is gracing three-Michelin-star dining tables in New York. Truly a rising star to watch closely.

José Pereiro López-Quecuty (Pepiño, for short, is a little easier) wears a few hats. Primarily, up until recently, he was one of the town pharmacists in Vigo in the Rías Baixas. In wine circles, he was known to lend a hand in the cellar of Raúl Pérez. In 2011, his own vinous vision came to fruition not with Albariño or Mencía but with the planting of a three-hectare amphitheater of Brancellao and Caíño Longo in Carballeda de Avia called O Gabián. For now, only a portion of that estate fruit is being bottled (as ‘Xanledo’), but as the roots dig deeper into the granitic sand it’s only going to get better; as it stands, the sheer elegance of the wine is already such that the lion’s share of it destined for American shores is gracing three-Michelin-star dining tables in New York. Truly a rising star to watch closely.