It might sound a little bit like New Age mumbo jumbo when someone tells you that they’re “…trying to do less,” but when Bruce Schneider says it – after spending more than an hour relating his unrepentant entrepreneurial history – it seems fair.

Long before the Gotham Project had wine flowing from taps across the country, Schneider was immersed in the wine world– both his father and uncle were in the New Jersey wine business, on the supplier and distributor side, throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s. It was his uncle, who represented the venerable Joseph Drouhin, that set him up with a high school trip to work for a few weeks in Burgundy. Bruce spent some time at Trebuchet, and then later with François Mikulski – who was only a few years older than his “intern,” although much more familiar with the pruning that was being done in the vineyards. Schneider made sure to come back after college, for the 1990 harvest.

Long before the Gotham Project had wine flowing from taps across the country, Schneider was immersed in the wine world– both his father and uncle were in the New Jersey wine business, on the supplier and distributor side, throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s. It was his uncle, who represented the venerable Joseph Drouhin, that set him up with a high school trip to work for a few weeks in Burgundy. Bruce spent some time at Trebuchet, and then later with François Mikulski – who was only a few years older than his “intern,” although much more familiar with the pruning that was being done in the vineyards. Schneider made sure to come back after college, for the 1990 harvest.

Many winemakers’ stories would then take a fairly predictable trajectory after an experience like that: work your way up in the cellar, take a winemaker job, leave to begin your own estate, etc. Schneider, though, had a bit more on his mind than Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, and although he dipped his toe into the family business selling wine on the street for six months, he ended up using his history major background to get into politics, beginning with an internship with Mario Cuomo, then the governor of New York. Not only did it turn into a real job, culminating in a role on the Clinton campaign in 1992, but it was while working for Cuomo that he met his wife, Christiane Baker, who worked in the press office. Meanwhile, though, Schneider hadn’t forgotten about wine, and despite the demands of the campaign was still taking Harriet Lembeck’s Wine & Spirits classes, working from Grossman’s Guide to Wines, Beers, and Spirits when Baker connected him with the New York Wine & Grape Foundation.

While visiting the North Fork Schneider was surprised to find, perhaps because of a decidedly Euro-centric diet of wine tasting, that his favorite wines at places like Hargrave (now part of Castello di Borghese) were the winemakers’ “afterthoughts”: tank-fermented Chardonnay, for example, and Cabernet Franc, both of which were just being held separately for blending with other lots later. He was intrigued, to say the least, and although they were just tank samples, they reminded him more of Chablis or Chinon than much else he’d tasted from the New World. He dove deeper into research.

In 1993 he left politics to move into public relations in the private sector; his main client initially being the wineries of South Africa, who were looking to penetrate the American market after the anti-apartheid embargo was lifted. Also saving for an engagement ring, though, he moonlighted at the retailer Garnet Wine, where the manager David Lillie, who later left for the esteemed Chambers Street Wines, asked upon meeting: “Can you sell Burgundy?”

Knowing the terroir intimately, Schneider managed to stick around long enough to be exposed to a whole set of other wines, including those Loire Valley expressions of Cabernet Franc that proved useful as a reference on the East End. It was a beguiling variety, the parent of all of the Bordelaise vines, and he began to think that what was traditionally an “afterthought” might be the “premier” variety of this developing region.

It was Baker’s father who first saw a listing for a property for sale on Long Island that showed promise, and although the transaction never happened, the due diligence that Schneider put in in anticipation was enough to begin the formulation of a plan. Eschewing the traditional model – which relied on a physical winery, tasting room, and lots of seasonal visitors – Schneider saw more potential in the mode of a négociant, or even, garagiste.

The first vintage of Schneider Vineyards was 1994, a mere two hundred cases of Cabernet Franc and a smaller amount of Merlot, and it was self-distributed. “I was naïve enough to think that I could just get in front of some of the city’s sommeliers, and that they would buy the wine based on its merits,” Schneider recalls. And they did. Paul Greico, who Schneider remembers meeting with in the cellar of Gramercy Tavern, was an early supporter; after a quick tasting, he decided to pour it by the glass.

In six months, they went through 25% of the total production, and by then it was on the list at a boldfaced list of about twenty NYC restaurants, including Gotham Bar & Grill and Le Cirque. The ’95 vintage earned 95 points from Wine Spectator, but, coupled with a tough, tiny vintage in ’96, the local reaction to Schneider Vineyards was not fully positive. Other producers were irritated by the attention this upstart was getting, and despite his obvious aptitude for marketing and lobbying, Schneider was excluded from the local wine council.

He described the divide succinctly, “These guys always said their wines were ‘local,’ and that that was why you should buy them.” Instead, Schneider wanted you to buy his Cabernet Franc because it was good, regardless of its origin.

Once again it would seem – in the traditional narrative – that he would be so busy with the winery that he would have put aside his other interests, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. In the same year that he picked his first fruit he founded his own PR firm, Schneider Integrated, and, by the third vintage, had applied to Columbia Business School. It was there that, in 1999, he won a prize from the Eugene Lang Entrepreneurial Initiatives Fund, based on the Schneider Vineyards business plan.

The problem, as he saw it, was that there wasn’t enough Cabernet Franc planted on Long Island to satisfy the demands of a financially viable winery, so he used the $250,000 prize as a down payment on a potato farm in Riverhead, which he planted to a mixture of Cabernet Franc clones. Although he changed his status at Columbia to part-time, he did eventually finish his MBA in 2001 – just as his priority became the family farm. He had the help of Sean Capiaux, now a star in Napa and Sonoma; but in those days Capiaux’s day job was at the North Fork’s Jamesport Winery, and this is who Schneider says he “…learned more about winemaking (from) than anyone else.” He left his partner in charge of the PR firm and moved with Christiane to the property the same year, where they both took on an aggressive amount of responsibility to farm the vineyard, producing its first crop in 2002. It was a hard year, in which Bruce and Christiane had to do more than they anticipated–there was an acute shortage of labor, Christiane gave birth to their first child, and if they had any time in between pruning rows it was spent taking care of city visitors in their slapdash tasting room, a barrel under a tent.

“It wasn’t the dream,” he will admit, candidly. Whether it was cultural, or a result of their unorthodox business strategy, they didn’t feel like part of the community. They missed the city and weren’t sure if they wanted to raise a family so far away from the city. They made the hard decision to move back to Brooklyn in 2003.

He got back into the PR business, including representing the wines of Germany, for which he still consults, and despite Christiane’s puissant position (“You cannot start another business!”) he saw the need for the South American growers and winemakers he was interacting with for another project to have better representation in the US. Schneider Selections, his importing company, was born. It was in these days, when he was already working with Skurnik as a distribution partner, that he got to know Charles Bieler, the itinerant winemaker whose restless spirit seemed to compliment Schneider’s; collaboration seemed natural.

He got back into the PR business, including representing the wines of Germany, for which he still consults, and despite Christiane’s puissant position (“You cannot start another business!”) he saw the need for the South American growers and winemakers he was interacting with for another project to have better representation in the US. Schneider Selections, his importing company, was born. It was in these days, when he was already working with Skurnik as a distribution partner, that he got to know Charles Bieler, the itinerant winemaker whose restless spirit seemed to compliment Schneider’s; collaboration seemed natural.

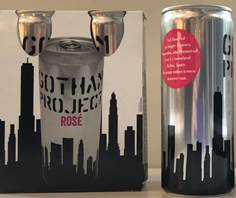

Bieler proposed a North Fork rosé, bringing Bieler’s touch with the style to Schneider’s familiarity with the region, but the latter wasn’t quite ready to jump back into the Long Island scene. A few months later Schneider received a call from Bieler who had just left a meeting with the wine buyer for Whole Foods, Devon Broglie, during which Broglie teased Bieler about not having done anything innovative in a couple of years–he challenged him to figure out a way to make wine on tap viable. Having a line on some Finger Lakes Riesling, Schneider was on board immediately, and thus began what he hopes to be his only gig someday: Gotham Project.

They hired designer Steven Solomon, who had given Grieco’s wine lists at Terroir their distinct look, and debuted at the Skurnik Grand Portfolio Tasting in 2010. The first run was 200 kegs for which the partners had each put up $10,000, and the project was greeted with some skepticism. When Grieco tasted the wine his response was succinct: “Fuck, yeah!!!” The wine first appeared on tap at Terroir Tribeca when it opened in April 2010.

It wasn’t smooth sailing, though, by any means. The initial marketing included an image of a middle finger identifying various lakes that was widely condemned by the Finger Lakes community, and some high-flying sommeliers and writers were derisive of the potential quality of any wine not served from a bottle. The latter claim was exacerbated by their naiveté in terms of the technology, and that first batch was plagued with issues; notably a sulfurous, rotten-egg smell in some cases, and there were some panicked tastings at the warehouse where the partners began calling each other “Doctor” as they worked furiously to save their sick kegs.

It wasn’t smooth sailing, though, by any means. The initial marketing included an image of a middle finger identifying various lakes that was widely condemned by the Finger Lakes community, and some high-flying sommeliers and writers were derisive of the potential quality of any wine not served from a bottle. The latter claim was exacerbated by their naiveté in terms of the technology, and that first batch was plagued with issues; notably a sulfurous, rotten-egg smell in some cases, and there were some panicked tastings at the warehouse where the partners began calling each other “Doctor” as they worked furiously to save their sick kegs.

Turns out, low-quality steel for kegs and semi-porous beer lines were not a good mix for wine. They worked hard to sort it out, and to this day the company’s team checks all setups before the juice is tapped.

“Charles is a different person, for sure, but when it comes to the things that matter, we’re always totally aligned.” The partnership thrived, and they sold out of the wine in six months. The demand was clearly there, and in addition to teaching the wine world about how to serve kegged wine, they pioneered the use of large bladders to ship thousands of liters of wine to their facility from South America, Europe, and the West Coast. Originally, they consolidated 1000L vessels into shipping containers, but as business grew, they began to use 24,000L bladders.

“The larger the vessel, the less headspace, and therefore less chance of oxidation and a higher quality glass for the guest,” Schneider explained, comparing these bladders to magnums or other large format wine bottles. With their new facility in Bayonne, they are working with 35 selections, have twelve full-time employees, and are distributed in almost every state in the US. Bieler continues to work on a number of products, but Schneider is trying his best to focus his energy on having just one job.

“The larger the vessel, the less headspace, and therefore less chance of oxidation and a higher quality glass for the guest,” Schneider explained, comparing these bladders to magnums or other large format wine bottles. With their new facility in Bayonne, they are working with 35 selections, have twelve full-time employees, and are distributed in almost every state in the US. Bieler continues to work on a number of products, but Schneider is trying his best to focus his energy on having just one job.

They sold the winery on Long Island, which was ripped out to become a horse farm; the silver lining is that the diverse genetic material of the vines was grafted over to what would become the Onabay Vineyard, where Schneider is still the consulting winemaker. As the vines have matured, the wines are exhibiting exactly the kinds of characteristics that brought him to the East End in the first place, but without the burden of maintaining the operation of one’s own farm and winery. He still does some work in the PR space as well, but after years of doing a lot of things at once, the next few years promise a little bit more of a simple life.

- Inspired by the Blanc de Blanc Champagnes of France

- Chardonnay carefully selected and hand harvested at early ripeness

- Traditional, old world method of inducing secondary fermentation in bottle

- Over 30 months en tirage

Onabay ‘Cot-Fermented’ Cabernet Franc 2016

- Two distinct clones of ripe Cabernet Franc and a small percentage of Malbec (aka Cot)

- Hand harvested on the same day, destemmed and soaked for two days

- The two grapes are co-fermented, a longstanding old world tradition

- Malolactic conversion in barrel

- Aged for 9 months in seasoned French oak

Schneider & Bieler ‘Le Breton’ Cabernet Franc 2017

- 100% Cabernet Franc from Seneca and Cayuga Lake

- Inspired by Bruce Schneider’s long-time passion for the grape

- Dedicated exclusively to two shades of Cab Franc grown on the best vineyard sites in the region

Gotham Project ‘El Rede’ Malbec 2017

- Hand-picked grapes from 90-year-old vines in the continental climate of Mendoza, Argentina

- Gently de-stemmed and fermented for 7 days

- Fermented in stainless steel

- Dry-farmed, old vine (80 plus years) Monastrell/Mourvèdre

- From the genetic homeland of the varietal, Bullas, in Murcia Spain

- Picked on the early edge of ripeness and made direct to press