Leo Alzinger Jr.’s path to winemaking began when he was very young, watching his mother and father in the vineyards and cellars of the family winery. “There were no employees at this time; it was just them. I loved this from the beginning, being outside, working in nature”. His interest deepened as he grew older and he attended school for viticulture at Klosterneuburg. During his studies he worked at several Austrian wineries including Malat and Jamek, in the Wachau.

Leo traveled to other regions to gain more experience, and was fortunate to spend time with legendary winemaker Hans Günter Schwarz just prior to his retirement in 2002. “The most significant experience came with my work in the Pfalz at Müller-Catoir in the vintage 2000. Hans Günter Schwarz revealed things in the cellar, small details which gave stronger impressions of vineyard and place. He taught me not to be afraid of skin contact, that good grapes will give good phenols, for example. How important work with the lees is and many other things.”

In 2002, after spending a harvest in New Zealand at Fromm winery, Leo Jr. returned to the family estate, committed to following the path of his father, focusing on the different terroirs in this part of the Wachau. Just as his father before him, Leo Alzinger Jr. concentrates on a pure expression of individual vineyard sites, showing the vintage character clearly without masking the terroir. “We produce the wines in a cooler, precise style, looking for clarity and elegance over raw power.”

THE SITES

Upon Leo’s return in 2002, his parents were farming “between 4 and 5 hectares. Over the last decade and a half, we have grown to 11.5 hectares. We bought small parcels from our neighbors, normally vineyards that are close to our own. Even our biggest parcel in a terraced vineyard is only .4 hectares. These are small pieces that we were able to acquire over time.”

Generally, the eastern Wachau is more influenced by the warm Pannonian climate from the east; 2 km downstream, the Danube bends, breaking these warmer winds. This of course is a generality and understanding the climactic conditions in this area is more nuanced. “Each vineyard almost has its own climate, which of course contributes to its character. It is not just soil that makes terroir, it is exposure, and the climate and many other factors that make a vineyard’s personality,” Leo notes.

For example, the Steinertal, at the eastern entrance to the Wachau, should theoretically have the warmest conditions; it is open to the east, where the Pannonian climate enters the valley. However, cold air from the north flows quickly into the vineyard through a side valley. In fact, Steinertal is one of the cooler vineyards in this part of the Wachau. Ravines also cut through to the Loibenberg vineyard and its elevation and proximity to the forest provides a counterpoint to the generally warm climate. Of course, within these vineyards there are different zones. Take Loibenberg, for example: “We have 80% of our Riesling planted in a subsection of Loibenberg called Rauheneck, which means ‘rough place’. It is higher up, protected, cooler and doesn’t ripen at the same time as the south facing part of the hill,” says Leo. The Liebenberg also demonstrates an exception. Although only few kilometers further to the west, the cool air coming from the Waldviertel forest to the north make this a much cooler site.

THE SOILS

While the climate plays a central role, the foundation of terroir and great wine, lies in the soil and subsoil that the vines are planted on. The Wachau has wide spectrum of soils and geological material in just a short length of river.

Weather changes year by year but the geological aspect of the vineyard remains stable. The eastern Wachau, where all of Alzinger’s vineyards are found, are predominantly gneiss though amphibolite, loess and sediments from the Danube also play a role.

Orthogneiss or Gföhl Gneiss: A granite-like rock metamorphosed into orthogneiss during the Variscan Orogeny, a mountain building event in the late Paleozoic. This is the period that also created the Paris Basin, the Voges and Haart mountains and Corsica. Orthogneiss soils are light, sandy, and warm quickly and evenly. Vines root easily in this light soil and water drains well. The resulting wines are elegant, light in body, with a fine structure. This is the basis for many of the vineyards from Steinertal, the 5.6 hectare vineyard and the first truly steep vineyard in the Wachau, just west of the village of Stein to Höhereck, the ridge between Kellerberg and Loibenberg in Dürnstein.

Paragneiss: West of Dünstein, paragneiss takes over the dominant role in the Wachau. Paragneiss is metamorphic rock that was formed from sedimentary rocks like marl, clay, and sandstone. It weathers into a light and sandy soil with excellent drainage. While it doesn’t store water well, it captures heat. Creamy texture and dark smoky notes are typical characteristics of wines that come from paragneiss. This soil type, with Amphibolite outcroppings make up the soils of the 10.15 hectare Liebenberg vineyard.

Amphibolite: Originating as submarine volcanoes, Amphibolite was formed from enormous heat from molten rock. Amphibolite is found not on its own, but often with Ortho and paragneiss. The vineyards between Weissenkirchen and Dürnstein. These sandy, iron-rich soils warm well and are also part of the composition of Liebenberg vineyard.

Loess: Loess is a windblown soil deposited from drainage basins during the last ice age. It’s found in many of the Wachau vineyard terraces. Quartz, feldspar, mica and limestone are all found in this soil type. Loess is very deep in some terraces and very thin in others. This is the main soil type for the Grüner Veltliner wines – Mühlpoint, and in the lower terraces of Loibenberg and Steinertal where loess is found.

IN THE VINEYARD

A majority of the vineyards at Alzinger are very steep, some so steep that machinery is impossible to use; handwork is a very important aspect of this work. Every vine – whether vigorous or sensitive, young or old, Grüner Veltliner or Riesling – is different and has different needs and must be tended individually.

“Wine is an interplay of natural preconditions and the wine growers’ persistent efforts in making the most authentic, unique, and wholesome wine possible. Decisions must be made daily, and sometimes the most difficult decisions are to consciously do nothing, to simply be patient and wait for the vine or the wine to develop on its own” says Leo.

Practicing “soft pruning” (a method from northern Italy that minimizes the amount of cutting and exposing the vine to open cuts), conscientious canopy management, responding to the weather in a responsible way and choosing the right time to harvest are all aspects in this process. The sum of all of these decisions are taken to find an ideal balance between acidity, body, alcohol and aroma.

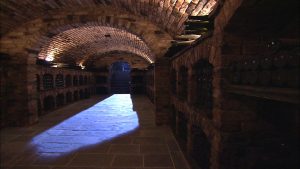

IN THE CELLAR

“Our efforts in the cellar are based on the same intentions that we practice in the vineyard – getting the balance we’ve achieved in the vineyard into the bottle. Vineyards are always more important than cellar work. In the cellar you can only lose quality; you cannot make poor grapes better in the cellar,” says Leo.

At harvest, the fruit is meticulously selected and sorted to remove botrytis, something that Alzinger has always done as the style of the wines here are about transparency and elegance rather than raw power. Botrytized Riesling and Grüner Veltliner are separated and set aside for two wines designated as Reserve, but without any vineyard designation. The healthy fruit is crushed but not destemmed before a short maceration on the skins contact. Skin contact depends on the vineyard and variety as well as the vintage, but generally Grüner Veltliner is on the skins for 3 or 4 hours and Riesling for 10-12 hours. After contact with the skins, the juice is pressed gently and the juice, which is slightly “browned”, settles for 12 hours. There is of course, no SO2 added prior to fermentation as the fermentations at Alzinger are generally spontaneous, though this depends on the health of the fruit. Fermentations range in length and are carried out in stainless steel, regardless of their vineyard or quality designation – both Smaragd and Federspiel are fermented in steel. After the alcoholic fermentation and a period of almost a month on the full lees, the wines are racked off the gross lees and into large, used Austrian Oak barrels for the Smaragd level wines and into stainless steel for the Federspiels for maturation. Smaragd’s are racked and bottled in late summer while the lighter Federspiels are bottled in March the year after the vintage.

“While I have not changed the style of the wines, I am always working towards more precision. We are doing maybe a little bit longer skin contact than my parents and a stricter selection, but it is the work in the vineyards that is most important. In the cellar we are stewards of the wines.”

“While I have not changed the style of the wines, I am always working towards more precision. We are doing maybe a little bit longer skin contact than my parents and a stricter selection, but it is the work in the vineyards that is most important. In the cellar we are stewards of the wines.”

Alzinger’s wines are never forceful or assertive; they are instead amazingly sanguine and calmly transparent.

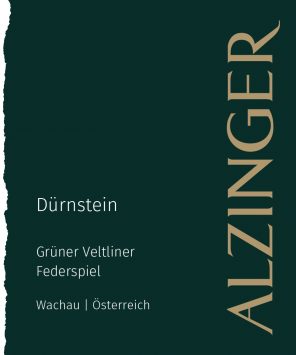

Alzinger Grüner Veltliner Dürnstein Federspiel

“I can’t remember a better vintage of this “basic” Federspiel. It has a wonderfully pretty fragrance leading to a stunningly expressive Federspiel; roasted haricot verts; firmly spicy but with secret-sweetness, into a solid stern finale. Everything the category could be, and seldom is.”

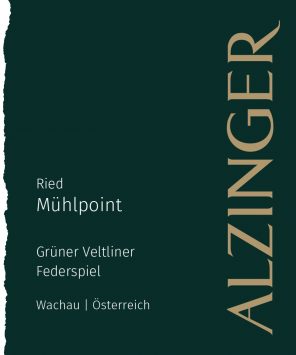

Grüner Veltliner Ried Mühlpoint Federspiel

“These wines really demonstrate the flattening out of the quality span we sometimes see in ’17, whereby the “light” wines ascend much closer to the “important” wines than usual. And yet unlike a year like, say, 2006, the top wines don’t get grotesque and over-alcoholic. For this wine is markedly expressive—in some years even the Smaragd isn’t this expressive. Roasty and dense with rich mineral texture, full of pepperiness and secret-sweetness.”

Grüner Veltliner Ried Mühlpoint Smaragd

“More compact and mineral and strong. Yes riper, yes more power, but compared to the Federspiel this is quite other in character, more of an edifice of white stone; not as much fruit but a greater volume of flavor, saltiness and garrigue.”

Grüner Veltliner Ried Loibenberg Smaragd

“Exotic and with “noble” stature, it’s given away by the charred-skin of a stovetop-roasted pepper and by the jalapeño warmth on the finish. For many tasters this will be a loaded grand sexy-pie wine, and to them I advise: drink it now and in its first year.”

Grüner Veltliner Ried Steinertal Smaragd

“’17 is a riper year for a sorrel-y silvery wine, showing less as lime and more as an orgy of greens in the mint family; nettle, the arugula variant called “rocquette,” mizuna, Italian parsley. The wine is decidedly dry, with a smoky finish.”

Riesling Dürnsteiner Federspiel

“Again an exceptionally good Federspiel! Solid, stony and lovely; salts and verbena and a complex finish of herbs, wintergreen, aloe and mineral.”

Riesling Ried Loibenberg Smaragd

“As always plum and malt, Chinese 5-spice, candy cap mushrooms; it’s large and dancy, less concentrated and more dispersed than Höhereck, but an aspect of elegance is likely to emerge when the wine is focused by bottling.”

Riesling Ried Hollerin Smaragd

“Essentially the lower slopes of Höhereck (and Kellerberg, obliquely), it gives the most apricot-driven Riesling among Alzinger’s Smaragds. This one starts out with greener flavors than usual until a Victoria-Falls of stone fruit overwhelms, generously and lovingly. But it’s not a soft love, glorious though it is. There’s also a rock slide Christmas-tree thing above (or below) the white peaches. I don’t recall a Hollerin this schizy, and I think it is wonderful.”

Riesling Ried Steinertal Smaragd

“Wild screaming lime aroma, and here’s the Physio “secret” sweetness to elevate this to the divine, though it’s a wild and savage divinity, maniacally vivid and spicy.”

Riesling Ried Liebenberg Smaragd, Alzinger

“Steep terraces upstream from Dürnstein, giving (as a rule) radish-y Riesling—like now. Sweet radishes, ginger and parsnip, like a Ricola-candy of Riesling; bracing and fun if you like being tickled with ice cubes while chewing a verbena leaf. And really, who doesn’t?”